Digital Forensics Incident Response (DFIR) is all about containing the threat, collecting, analyzing, and preserving digital evidence, and remediating the issues that allowed the incident to occur. It’s a key part of investigating cybersecurity incidents and helps teams figure out what happened before, during, and after the attack. Basically, it helps organizations get off the “X” — the danger zone where they’re most vulnerable.

At its core, DFIR involves gathering data from various sources like computers, phones, servers, or cloud services and analyzing that information to uncover the actions of the attacker. This data can range from file metadata to system logs, each providing clues that help build a clear picture of the incident. Every piece of evidence has its own unique characteristics, and investigators use this info to pinpoint the malicious activity that triggered the breach and assess its impact.

For DFIR to be effective, handling evidence properly is essential—especially if it’s needed for legal proceedings. That means following strict protocols to maintain the chain of custody and ensuring the use of reliable forensic tools. Adhering to these guidelines ensures that the evidence remains intact and credible, which is vital if it’s ever presented in court or used to support legal action.

The DFIR process generally unfolds in key stages: preparation, detection (collection/analysis), containment, eradication, and recovery. Preparation focuses on setting up clear policies and defining responsibilities before an attack ever happens. Once an incident is detected, then collection and analysis of data begins to assist in swift containment that limits the damage. Take note that collection / analysis of data can occur rapidly.

An example of this would be during regular log review it is identified that a user’s account had over 100 failed login attempts in the span of 10 seconds. Then it was able to login. Based on knowing that it is very difficult for a user to type in their password wrong that many times in such a short timeframe the containment would be to disable the account and then start identifying what the user in question did once they successfully logged on.

Afterward all of the user’s activity has been identified and containment has completed then eradication will tackle the root cause. Finally, recovery involves bringing systems back to normal and refining strategies to prevent future incidents. This is a high level over view of the process and each step can be very in-depth. Overall this is a holistic approach that ensures organizations are not just reacting to threats but learning and adapting to build stronger security practices.

Common Pitfalls in DFIR

DFIR isn’t without its challenges, and one of the most common pitfalls is over-complicating the process. With the massive amount of data involved in any given incident, investigators can easily get overwhelmed and lose track of the investigation’s goals. This data overload can lead to confusion, wasted time, and missed key insights. To avoid this, it’s crucial to clearly define “what is know” from the very beginning.

An example of this would be, you are not going into an investigation blind. The victim has some information that allows them to identify they have been or potentially have been breached or else you would not be there.

- They have a user that clicked on an unknown link

- Files were accessed on X date and time that are not normally accessed by a user

- Company data was identified for sale on the dark web, where does that data reside normally in the environment

- A suspicious email was received by everyone in the company that contained a word doc

Always attempt to narrow the above down to timeframes, user accounts, files etc. From that you can strategically focus your investigation. By setting clear parameters, investigators can stay focused on the most relevant data and avoid getting sidetracked by unnecessary details.

Another pitfall is miscommunication which can significantly hinder the progress of a DFIR investigation, often leading to wasted time and effort. When roles and responsibilities aren’t clearly defined, team members may unintentionally duplicate tasks or overlook critical steps, which can compromise the investigation’s overall effectiveness. This lack of coordination can result in confusion, missed opportunities to gather vital evidence, or delays in responding to the threat.

In complex cases, where different areas of expertise—such as network security, data analysis, and legal considerations—need to work together seamlessly, clear communication and collaboration are absolutely essential. Effective teamwork ensures that each aspect of the incident is addressed thoroughly and that every team member knows their role in the larger picture. By fostering open communication and assigning clear responsibilities, DFIR teams can avoid costly mistakes and ensure a more streamlined and successful investigation.

Starting Your Investigation with What You Know (Scoping)

When launching a DFIR investigation, it’s smart to start with what you already know, like the context of the incident and any early indicators of compromise (IoCs). This approach helps keep the investigation focused and efficient.

A good place to begin is with timestamps. They can show when a breach happened, helping you create a timeline of events (covered more in a later section). Unusual access patterns at specific times might give clues about other malicious activity. I know many of you will say “well how do I begin with something that I don’t know” and you would be correct. You don’t know it, but as stated in the previous section, the victim knows something or they wouldn’t have called you. Ask them:

- What lead you to believe you were breached?

- When the email was received?

- When did the user click on the link?

- When was the malicious file(s) created on the system?

- What alerts did your EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) show?

- Did your AV (AntiVirus) alert, when and why ?

- Etc.

User behavior is a critical piece of the puzzle. Analyzing what users were doing on the system before the incident can help identify any odd actions that don’t fit with their usual habits. For example, if someone who typically handles HR files starts downloading sensitive data from engineering, that’s a red flag.

Examining executed files around the time of the breach can also help. By checking file hashes, investigators can determine if the files are legitimate or part of a malware attack.

Collecting and Preserving Evidence

In DFIR, gathering and preserving evidence is critical (if you haven’t noticed every step is “critical” 😊). It’s all about collecting data, whether it’s computer files or network logs, and making sure it stays intact so it’s usable in legal proceedings. This requires following strict protocols to avoid any data loss or corruption.

One of the key practices is using write-blockers to prevent any changes to the original data during copying. This ensures that the original evidence remains untouched while analysts work on duplicates. NEVER WORK ON THE ONLY COPY OF THE EVIDENCE.

Keeping detailed records of every step taken during evidence collection is also important, as this supports the chain of custody and adds credibility to the investigation. The right tools, like forensic imaging software and hashing algorithms, help ensure the accuracy of the data. Checklists can also be useful to make sure no critical steps are missed.

Performing a Structured Analysis

As you start working the investigation do not throw darts into the darkness. What I mean by that is if you are looking at a file, user, computer, etc. have a reason to be looking at it. Don’t just aimlessly start walking through the data in hopes of stumbling upon bad. Use intel provided by the victim to scope, use tools to help process the data (av / IOC scanners), use known attack methodology, use anything other than just walking in the dark and hoping to fall upon the bad guy.

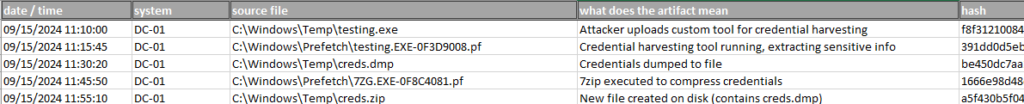

Second start a timeline. Fire up an excel spreadsheet and set the headers to something like the following:

You won’t always have a clear understanding of what is or isn’t malicious or directly related to the investigation. In these cases, it’s essential to rely on your best judgment, drawing on what you’ve already uncovered about the current attack and your experience with similar incidents. When you’re uncertain, it’s better to err on the side of caution and include potentially relevant data in your timeline. Doing this will reduce the likelihood that you overlook critical details that could become important later on. If you’ve done a thorough job during the scoping phase, you’ll have already filtered out much of the irrelevant information, minimizing the chances of being overwhelmed by unimportant data. Once you’ve sorted the artifacts by time, patterns will start to emerge, and it will become clearer which events are part of the attack and which aren’t, allowing you to focus on the key pieces of evidence.

“There is still a lot to learn and there is always great stuff out there. Even mistakes can be wonderful.” – Robin Williams